Microsoft’s recent study on careers most likely to be augmented by AI has sparked debate, especially after “historian” ranked second on the list. The finding led many to assume that historians may soon be replaced by machines, prompting a wave of concern and curiosity across social media. However, augmentation does not necessarily mean obsolescence. To test the claim, I put several generative AI tools through their paces with historical facts and context.

The results suggest that while AI can assist with certain tasks, it lacks the nuance, interpretation, and critical analysis that define the historian’s craft. For now, historians can rest assured: the robots aren’t ready to take their jobs at least, not in any meaningful or competent way.

Read More: Breakfast with ChatGPT: Three Workers, One Morning, and a Unique AI Experience

Presidential movies

When deciding what historical facts to test, I turned to one of my long-standing fascinations: the movies U.S. presidents have watched while in office. It’s a niche interest, admittedly, but one I’ve pursued since 2012, when I first stumbled across a list of films Ronald Reagan viewed at the White House and Camp David.

That discovery inspired me to file a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request for Barack Obama’s viewing history only to learn that presidential records remain exempt from FOIA until five years after a president leaves office. Undeterred, I dug deeper, tracing presidential movie habits back to Teddy Roosevelt’s first screening a bird documentary in 1908.

When testing generative AI, it’s best to use a subject you know intimately. Most people ask AI about unfamiliar topics, which makes sense; these tools promise to save time and improve results. If they worked as advertised, they’d be extraordinary. The problem? Too often, they don’t. I asked both simple, Google-able questions and obscure ones requiring archival sleuthing. The answers revealed just how unreliable AI can be when accuracy actually matters.

OpenAI’s GPT-5 flopped

I began my testing with OpenAI’s GPT-5, posing what I thought were straightforward questions: what movies did various presidents watch on specific dates? I selected examples from the administrations of Woodrow Wilson, Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush. Each time, ChatGPT responded that it could find no record of any screenings on those dates.

At least it didn’t fabricate answers a habit these tools have been known for but it still failed to deliver on fairly basic queries. GPT-5 is now available to all free users, yet OpenAI offers little transparency about which underlying model is actually responding. When I asked about specific dates, it was unclear what was happening “under the hood.”

The rollout hasn’t gone smoothly. CEO Sam Altman promised GPT-5 would be like having “a legitimate PhD-level expert in anything” on demand, but the removal of the option to select older models disrupted countless workflows, frustrating power users. After backlash, OpenAI reinstated access to GPT-4o for subscribers. Even so, my results suggest that if you need unique, accurate answers without paying for a subscription, GPT-5 isn’t there yet.

Some argue the only reason CEOs haven’t replaced human workers wholesale with AI is to avoid the bad optics of mass layoffs. That theory feels hollow. The reality is simpler: these tools still require human oversight because they make too many errors, too often. My tests with Google Gemini, Microsoft Copilot, Perplexity, and xAI’s Grok confirmed the pattern none were flawless. Executives may accept “good enough” for many tasks, but when accuracy is critical, humans remain indispensable.

Eisenhower and Grok’s surprising answer

After ChatGPT’s poor showing, I turned to Microsoft Copilot, which lets users search with various OpenAI models and offers a “Deep Research” mode that can take up to ten minutes to produce a report. I ran the same presidential movie questions I had used with GPT-5 first with Quick Response (powered by GPT-4o), then with Deep Research.

Quick Response mode was a disaster from the start. When I asked what movie President Eisenhower watched on August 11, 1954, Copilot confidently claimed it was The Unconquered, a documentary about Helen Keller. That’s incorrect, though Eisenhower does appear briefly in archival footage, which may have confused the AI.

Deep Research mode was just as wrong—only much longer. It produced over 3,500 words, reasoning that Eisenhower “probably” watched Suddenly. That’s an odd choice given that Suddenly wasn’t released until October 7, 1954, months after the date in question. Copilot seemed to assume a movie must have been shown simply because I asked. From its own report:

The balance of circumstantial and secondary evidence points to “Suddenly” as the film President Eisenhower watched on August 11, 1954…

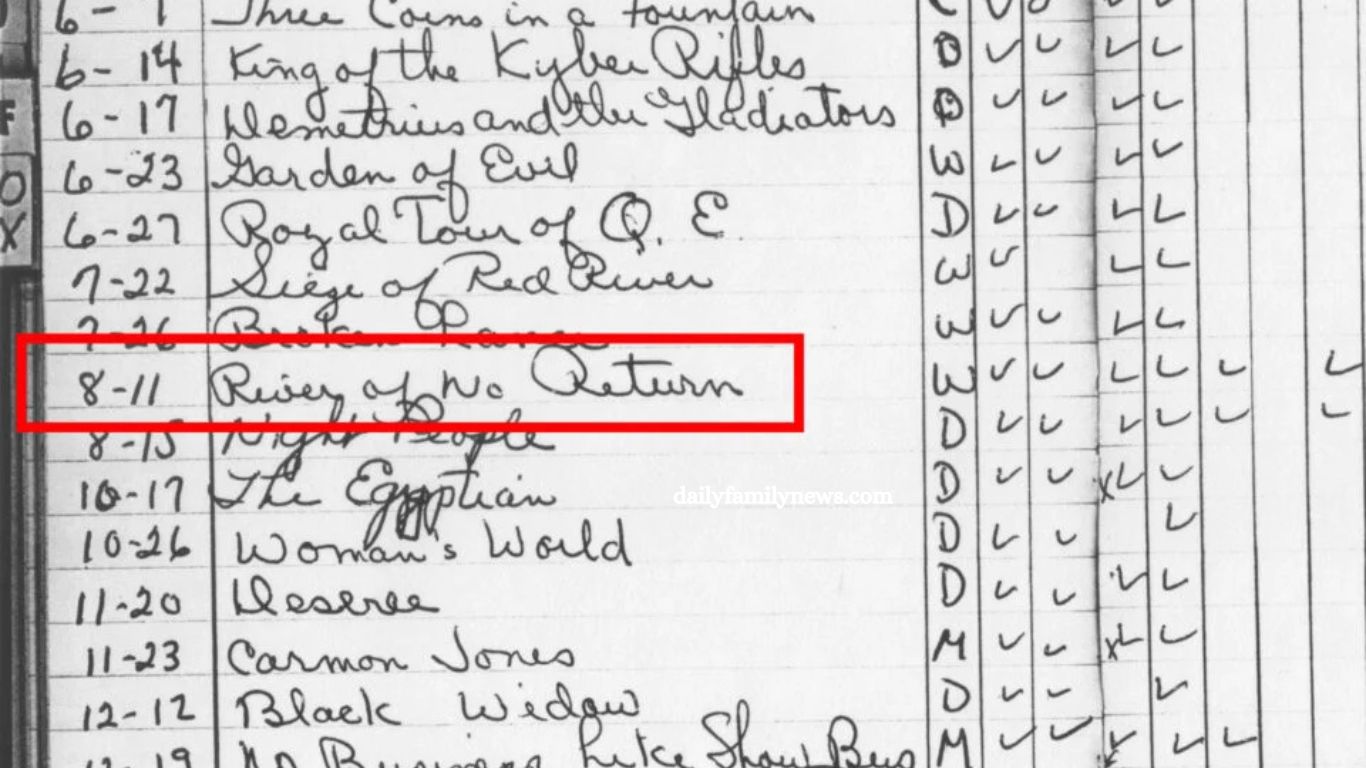

That’s not evidence it’s guesswork. In reality, I know exactly what he watched, thanks to the White House projectionist’s logbook from the 1950s. On that date, Eisenhower viewed River of No Return, directed by Otto Preminger and starring Marilyn Monroe and Robert Mitchum.

Other chatbots didn’t fare much better. Google Gemini had no answer. Perplexity also guessed Suddenly, likely because Wikipedia notes that the film’s writer, Richard Sale, got the idea while reading about Eisenhower’s trips to Palm Springs a coincidence that seems to have misled both Copilot and Perplexity.

Surprisingly, xAI’s Grok got it right but only after I clicked “think harder.” Its source? My own 2019 tweet from All the Presidents’ Movies.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why focus on historians specifically?

Historians rely on interpretation, context, and critical analysis—skills AI still struggles to replicate reliably.

Can AI ever replace historians in the future?

While AI can assist with data gathering and pattern recognition, replacing historians entirely would require human-like judgment and nuanced reasoning, which AI currently lacks.

How does AI perform on historical questions?

Tests show that generative AI often produces inaccurate or fabricated answers, especially when information is rare, obscure, or poorly documented.

Why not just use AI for quick research?

Quick AI research can be useful, but without verification from credible sources, there’s a risk of spreading misinformation.

What’s the biggest takeaway from your tests?

AI tools are best used as assistants, not replacements—especially in fields where accuracy and interpretation are paramount.

Conclusion

AI tools have made remarkable progress, but my experiments with presidential movie trivia show just how often they still miss the mark. From confident but wrong guesses to elaborate justifications built on shaky assumptions, these systems remind us that speed and polish aren’t the same as accuracy. Historians and anyone working with nuanced, factual material offer something AI can’t: the ability to interpret evidence, understand context, and know when the most truthful answer is “there’s no record.”